History of the Jews in the United States

Until the 1830s, the Jewish community of Charleston, South Carolina, was the largest in North America. In the late 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s, many Jewish immigrants arrived from Europe. For example, many German Jews arrived in the middle of the 19th century, established clothing stores in towns across the country, formed Reform synagogues, and were active in banking in New York. Immigration of Eastern Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews, in 1880–1914, brought a new wave of Jewish immigration to New York City, including many who became active in socialism and labor movements, as well as Orthodox and Conservative Jews.

Refugees arrived from diaspora communities in Europe after the Holocaust and, after 1970, from the Soviet Union. Politically, American Jews have been especially active as part of the liberal New Deal coalition of the Democratic Party since the 1930s, although recently there is a conservative Republican element among the Orthodox. They have displayed high education levels and high rates of upward social mobility compared to several other ethnic and religious groups inside America. The Jewish communities in small towns have declined, with the population becoming increasingly concentrated in large metropolitan areas. Antisemitism in the U.S. has endured into the 21st century, although numerous cultural changes have taken place such as the election of many Jews into governmental positions at the local, state, and national levels.

In the 1940s, Jews comprised 3.7% of the national population. As of 2019, at about 7.1 million, the population is 2% of the national total—and shrinking as a result of low birth rates and Jewish assimilation. The largest Jewish population centers are the metropolitan areas of New York (2.1 million), Los Angeles (617,000), Miami (527,750), Washington, D.C. (297,290), Chicago (294,280) and Philadelphia (292,450).[3]

Jewish immigration

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

The Jewish population of the U.S. is the product of waves of immigration primarily from diaspora communities in Europe; emigration was initially inspired by the pull of American social and entrepreneurial opportunities, and later was a refuge from the peril of ongoing antisemitism in Europe. Few ever returned to Europe, although committed advocates of Zionism have made aliyah to Israel.[4] Statistics demonstrate that there was a myth that no Jews returned to their previous diasporic lands, but while the rate was around 6%, it was much lower than for other ethnic groups.[5]

From a population of 1,000–2,000 Jewish residents in 1790, mostly Sephardic Jews who had immigrated to Great Britain and the Dutch Republic, the American Jewish community grew to about 15,000 by 1840,[6] and to about 250,000 by 1880. Most of the mid-19th century Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants to the U.S. came from diaspora communities in German-speaking states, in addition to the larger concurrent Christian German migration. They initially spoke German, and settled across the nation, assimilating with their new countrymen; the Jews among them commonly engaged in trade, manufacturing, and operated dry goods (clothing) stores in many cities.

Between 1880 and the start of World War I in 1914, about 2,000,000 Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews immigrated from diaspora communities in Eastern Europe, where repeated pogroms made life untenable. They came from Jewish diaspora communities of Russia, the Pale of Settlement (modern Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova), and the Russian-controlled portions of Poland. The latter group clustered in New York City, created the garment industry there, which supplied the dry goods stores across the country, and were heavily engaged in the trade unions. They immigrated alongside indigenous eastern and southern European immigrants, which was unlike the historically predominant American demographic from northern and western Europe; Records indicate between 1880 and 1920 that these new immigrants rose from less than five percent of all European immigrants to nearly 50%. This feared change caused renewed nativist sentiment, the birth of the Immigration Restriction League, and congressional studies by the Dillingham Commission from 1907 to 1911. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 established immigration restrictions specifically on these groups, and the Immigration Act of 1924 further tightened and codified these limits. With the ensuing Great Depression, and despite worsening conditions for Jews in Europe with the rise of Nazi Germany, these quotas remained in place with minor alterations until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Jews quickly created support networks consisting of many small synagogues and Ashkenazi Jewish Landsmannschaften (German for "Territorial Associations") for Jews from the same town or village.

Leaders of the time urged assimilation and integration into the wider American culture, and Jews quickly became part of American life. During World War II, 500,000 American Jews, about half of all Jewish males between 18 and 50, enlisted for service, and after the war, Jewish families joined the new trend of suburbanization, as they became wealthier and more mobile. The Jewish community expanded to other major cities, particularly around Los Angeles and Miami. Their young people attended secular high schools and colleges and met non-Jews, so that intermarriage rates soared to nearly 50%. Synagogue membership, however, grew considerably, from 20% of the Jewish population in 1930 to 60% in 1960.

The earlier waves of immigration and immigration restriction were followed by the Holocaust that destroyed most of the European Jewish community by 1945; these also made the United States the home for the largest Jewish diaspora population in the world. In 1900 there were 1.5 million American Jews; in 2005 there were 5.3 million. See Historical Jewish population comparisons.

The most recent Jewish communities to immigrate to the United States en masse are Iranian Jews, who primarily immigrated to the United States in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution, and Soviet Jews who came after the fall of the Soviet Union.[7]

On a theological level, American Jews are divided into a number of Jewish denominations, of which the most numerous are Reform Judaism, Conservative Judaism and Orthodox Judaism. However, roughly 25% of American Jews are unaffiliated with any denomination.[8] Conservative Judaism arose in America and Reform Judaism was founded in Germany and popularized by American Jews.

Colonial era[edit]

Luis de Carabajal y Cueva, a Spanish conquistador and converso first set foot in what is now Texas in 1570. The first Jewish-born person to set foot on American soil was Joachim Gans in 1584. Elias Legarde (a.k.a. Legardo) was a Sephardic Jew who arrived at James City, Virginia, on the Abigail in 1621.[9] According to Leon Huhner, Legarde was from Languedoc, France, and was hired to go to the Colony to teach people how to grow grapes for wine.[10] Elias Legarde was living in Buckroe in Elizabeth City in February 1624. Legarde was employed by Anthonie Bonall, who was a French silk maker and vigneron (cultivator of vineyards for winemaking), one of the men from Languedoc sent to the colony by John Bonall, keeper of the silkworms of King James I.[11] In 1628, Legarde leased 100 acres (40 ha) on the west side of Harris Creek in Elizabeth City.[12] Josef Mosse and Rebecca Isaake are documented in Elizabeth City in 1624. John Levy patented 200 acres (81 ha) of land on the main branch of Powell's Creek, Virginia, around 1648, Albino Lupo who traded with his brother, Amaso de Tores, in London. Two brothers named Silvedo and Manuel Rodriguez are documented to be in Lancaster County, Virginia, around 1650.[13] None of the Jews in Virginia were forced to leave under any conditions.

Solomon Franco, a Jewish merchant, arrived in Boston in 1649; subsequently, he was given a stipend from the Puritans there, on the condition that he leave on the next passage back to Holland.[14] In September 1654, shortly before the Jewish New Year, twenty-three Jews from the Sephardic community in the Netherlands, coming from Recife, Brazil, then a Dutch colony, arrived in New Amsterdam (New York City). Governor Peter Stuyvesant tried to enhance his Dutch Reformed Church by discriminating against other religions, but religious pluralism was already a tradition in the Netherlands and his superiors at the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam overruled him.[15] In 1664 the English conquered New Amsterdam and renamed it New York.

Religious tolerance was also established elsewhere in the colonies. The charter of the colony of South Carolina granted liberty of conscience to all settlers, expressly mentioning "Jews, heathens, and dissenters."[16] As a result, Charleston, South Carolina has a particularly long history of Sephardic settlement,[17] which, in 1816, numbered over 600—then the largest Jewish population of any city in the United States.[18] Sephardic Dutch Jews were also among the early settlers of Newport (where Touro Synagogue, the country's oldest surviving synagogue building, stands), Savannah, Philadelphia and Baltimore.[19] In New York City, Congregation Shearith Israel is the oldest continuous congregation started in 1687 having their first synagogue erected in 1728, and its current building still houses some of the original pieces of that first.[20]

Revolutionary era[edit]

By the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1776, around 2,000 Jews lived in the British North American colonies, most of them Sephardic Jews who immigrated from the Dutch Republic, Great Britain, and the Iberian Peninsula. Many American Jews supported the Patriot cause, with some enlisting in the Continental Army; South Carolinian planter Francis Salvador became the first American Jew to be killed in action during the war, while businessman Haym Solomon joined the New York branch of the Sons of Liberty and became one of the key financiers to the Continental Army.[21][22] The highest ranking Jewish officer in the Patriot forces was Colonel Mordecai Sheftall; whether or not Brigadier general Moses Hazen was Jewish is still the subject of debate among historians.[23][24] Other American Jews, including David Franks, suffered from their association with Continental Army officer Benedict Arnold (Franks served Arnold as an aide-de-camp) during his defection to the British in 1780.[citation needed]

U.S. President George Washington remembered the Jewish contribution when he wrote to the Sephardic congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, in a letter dated August 17, 1790:

A small Jewish community had developed in Newport over the 18th century; this included Aaron Lopez, a Jewish merchant who played a significant role in the town's involvement in the slave trade.[25]

In 1790, the approximate 2,500-strong American Jewish community faced a number of legal restrictions in various states that prevented non-Christians from holding public office and voting, though the state governments of Delaware, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Georgia soon eliminated these barriers, as did the U.S. Bill of Rights in 1791 more generally. Sephardic Jews became active in community affairs in the 1790s, after achieving "political equality in the five states in which they were most numerous."[26] Other barriers did not officially fall for decades in the states of Rhode Island (1842), North Carolina (1868), and New Hampshire (1877). Despite these restrictions, which were often enforced unevenly, there were really too few Jews in 17th- and 18th-century America for anti-Jewish incidents to become a significant social or political phenomenon at the time. The evolution of Jews from toleration to full civil and political equality that followed the American Revolution helped ensure that antisemitism would never become as common as in Europe.[27]

19th century[edit]

Following traditional religious and cultural teachings about improving a lot of their brethren, Jewish residents in the United States began to organize their communities in the early 19th century. Early examples include a Jewish orphanage set up in Charleston, South Carolina in 1801, and the first Jewish school, Polonies Talmud Torah, established in New York in 1806. In 1843, the first national secular Jewish organization in the United States, the B'nai B'rith was established.

Jewish Texans have been a part of Texas History since the first European explorers arrived in the 16th century.[28] Spanish Texas did not welcome easily identifiable Jews, but they came in any case. Jao de la Porta was with Jean Laffite at Galveston, Texas in 1816, and Maurice Henry was in Velasco in the late 1820s. Jews fought in the armies of the Texas Revolution of 1836, some with Fannin at Goliad, others at San Jacinto. Dr. Albert Levy became a surgeon to revolutionary Texan forces in 1835, participated in the capture of Béxar, and joined the Texas Navy the next year.[28]

By 1840, Jews constituted a tiny, but nonetheless stable, middle-class minority of about 15,000 out of the 17 million Americans counted by the U.S. Census. Jews intermarried rather freely with non-Jews, continuing a trend that had begun at least a century earlier. However, as immigration increased the Jewish population to 50,000 by 1848, negative stereotypes of Jews in newspapers, literature, drama, art and popular culture grew more commonplace, and physical attacks became more frequent.

During the 19th century, (especially the 1840s and 1850s), Jewish immigration was primarily of Ashkenazi Jews from Germany, bringing a liberal, educated population that had experience with the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment. It was in the United States during the 19th century that two of the major branches of Judaism were established by these German immigrants: Reform Judaism (out of German Reform Judaism) and Conservative Judaism, in reaction to the perceived liberalness of Reform Judaism.

Civil War[edit]

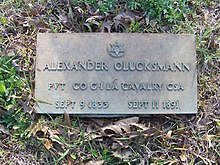

During the American Civil War, approximately 3,000 Jews (out of around 150,000 Jews in the United States) fought on the Confederate side and 7,000 fought on the Union side.[29] Jews also played leadership roles on both sides, with nine Jewish generals serving in the Union Army, the most notable of whom were brigadier generals Edward Solomon (who attained the rank at the age of 29) and Frederick Knefker.[30][31] There were also twenty-one Jewish colonels who fought for the Union, including Marcus M. Spiegel of Ohio.[32] and Max Friedman, who commanded the 65th Pennsylvania Regiment, 5th Cavalry, known as Cameron's Dragoons or the Cameron Dragoons, which had a sizable number of German Jewish immigrants from Philadelphia in its ranks.[33] Several dozens of Jewish officers also fought for the Confederacy, most notably Colonel Abraham Charles Myers, a West Point graduate and quartermaster general of the Confederate Army.[34]

Judah P. Benjamin served as Secretary of State and acting Secretary of War of the Confederacy.

Several Jewish bankers played key roles in providing government financing for both sides of the Civil War: Speyer and Seligman family for the Union, and Emile Erlanger and Company for the Confederacy.[35]

In December 1862 Major General Ulysses S. Grant, angry at the illegal trade in smuggled cotton, issued General Order No. 11 expelling Jews from areas under his control in western Tennessee, Mississippi and Kentucky:

Jews appealed to President Abraham Lincoln, who immediately ordered General Grant to rescind the order. Sarna notes that there was a "surge in many forms of anti-Jewish intolerance" at the time. Sarna, however, concludes that the long-term implications were highly favorable, for the episode:

Participation in politics[edit]

Jews also began to organize as a political group in the United States, especially in response to the United States reaction to the 1840 Damascus Blood Libel. The first Jewish member of the United States House of Representatives, Lewis Charles Levin, and Senator David Levy Yulee, were elected in 1845 (although Yulee converted to Episcopalianism the following year). Official government antisemitism continued, however, with New Hampshire only offering equality to Jews and Catholics in 1877,[37] the last state to do so.

Grant very much regretted his wartime order; he publicly apologized for it. When he became president in 1869, he set out to make amends. Sarna argues:

Banking[edit]

In the middle of the 19th century, a number of German Jews founded investment banking firms which later became mainstays of the industry. Most prominent Jewish banks in the United States were investment banks, rather than commercial banks.[39] Important banking firms included Goldman Sachs (founded by Samuel Sachs and Marcus Goldman), Kuhn Loeb (Solomon Loeb and Jacob Schiff), Lehman Brothers (Henry Lehman), Salomon Brothers, and Bache & Co. (founded by Jules Bache).[40] J. & W. Seligman & Co. was a large investment bank from the 1860s to the 1920s. By the 1930s, Jewish presence in private investment banking had diminished dramatically.[41]

Western settlements[edit]

In the nineteenth-century, Jews began settling throughout the American West. The majority were immigrants, with German Jews comprising most of the early nineteenth-century wave of Jewish immigration to the United States and therefore to the Western states and territories, while Eastern European Jews migrated in greater numbers and comprised most of the migratory westward wave at the close of the century.[42] Following the California Gold Rush of 1849, Jews established themselves prominently on the West Coast, with important settlements in Portland, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; and especially San Francisco, which became the second-largest Jewish city in the nation.[43]

Eisenberg, Kahn, and Toll (2009) emphasize the creative freedom Jews found in western society, unburdening them from past traditions and opening up new opportunities for entrepreneurship, philanthropy, and civic leadership. Regardless of origin, many early Jewish settlers worked as peddlers before establishing themselves as merchants.[44] Numerous entrepreneurs opened shop in large cities like San Francisco to service the mining industry, as well as in smaller communities like Deadwood, South Dakota and Bisbee, Arizona, which sprung up throughout the resource-rich West. The most popular specialty was clothing merchant, followed by the small-scale manufacturing and general retailing. For example, Levi Strauss (1829 – 1902) started as a wholesale dealer in with clothing, bedding, and notions; by 1873 he introduced the first blue jeans, an immediate hit for miners, and later, informal urban wear.[45] Everyone was a newcomer, and the Jews were generally accepted with few signs of discrimination, according to Eisenberg, Kahn, and Toll (2009).

Though many Jewish immigrants to the West found success as merchants, others worked as bankers, miners, freighters, ranchers, and farmers.[42] Otto Mears helped to build railroads across Colorado, while Solomon Bibo became the governor of the Acoma Pueblo Indians. Though these are by no means the only two Jewish immigrants to make names for themselves in the West, they help to showcase the wide variety of paths that Jewish settlers pursued. Organizations like the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and Baron Maurice de Hirsch's Jewish Agricultural Society served as a conduit for connecting Jewish newcomers arriving from Europe with settlements in the Upper Midwest, Southwest, and Far West. In other cases, family connections served as the primary network drawing more Jews to the West.[46]

Jeanette Abrams argues persuasively that Jewish women played a prominent role in the establishment of Jewish communities throughout the West.[47] For example, the first synagogue in Arizona, Tucson's Temple Emanu-El, was established by the local Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society, as was the case for many synagogues in the West. Likewise, many Jewish activists and community leaders became prominent in municipal and state politics, winning election to public office with little attention paid to their Jewish identity. They set up Reform congregations and generally gave little support to Zionism down to the 1940s.[48]

In the 20th century, Metropolitan Los Angeles became the second-largest Jewish base in the United States. The most dramatic cast of newcomers there was in Hollywood, where Jewish producers were the dominant force in the film industry after 1920.[49]

1880–1925[edit]

Immigration of Ashkenazi Jews[edit]

None of the early migratory movements assumed the significance and volume of that from Russia and neighboring countries. Between the last two decades of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth century, there was a mass emigration of Jewish peoples from Eastern and Southern Europe.[50] During that period, 2.8 million European Jews immigrated to the United States, with 94% of them coming from Eastern Europe.[51] This emigration, mainly from diaspora communities in Russian Poland and other areas of the Russian Empire, began as far back as 1821, but did not become especially noteworthy until after German immigration fell off in 1870. Though nearly 50,000 Russian, Polish, Galician, and Romanian Jews went to the United States during the succeeding decade, it was not until the pogroms, anti-Jewish riots in Russia, of the early 1880s, that the immigration assumed extraordinary proportions. From Russia alone the emigration rose from an annual average of 4,100 in the decade 1871–80 to an annual average of 20,700 in the decade 1881–90. Antisemitism and official measures of persecution over the past century combined with the desire for economic freedom and opportunity have motivated a continuing flow of Jewish immigrants from Russia and Central Europe over the past century.

The Russian pogroms, beginning in 1900, forced large numbers of Jews to seek refuge in the U.S. Though most of these immigrants arrived on the Eastern seaboard, many came as part of the Galveston Movement, through which Jewish immigrants settled in Texas as well as the western states and territories.[52] In 1915, the circulation of the daily Yiddish newspapers was half a million in New York City alone, and 600,000 nationally. In addition, thousands more subscribed to the numerous weekly Yiddish papers and the many magazines.[53] Yiddish theater was very well attended and provided a training ground for performers and producers who moved to Hollywood in the 1920s.[54][55]

Response to Russian pogroms[edit]

Repeated large-scale murderous pogroms in the late 19th and early 20th century increasingly angered American opinion.[56] The well-established German Jews in the United States, although they were not directly affected by the Russian pogroms, were well organized and convinced Washington to support the cause of Jews in Russia.[57][58] Led by Oscar Straus, Jacob Schiff, Mayer Sulzberger, and Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise, they organized protest meetings, issued publicity, and met with President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of State John Hay. Stuart E. Knee reports that in April, 1903, Roosevelt received 363 addresses, 107 letters, and 24 petitions signed by thousands of Christians leading public and church leaders—they all called on the Tsar to stop the persecution of Jews. Public rallies were held in scores of cities, topped off at Carnegie Hall in New York in May. The Tsar retreated a bit and fired one local official after the Kishinev pogrom, which Roosevelt explicitly denounced. But Roosevelt was mediating the war between Russia and Japan and could not publicly take sides. Therefore, Secretary Hay took the initiative in Washington. Finally Roosevelt forwarded a petition to the Tsar, who rejected it claiming the Jews were at fault. Roosevelt won Jewish support in his 1904 landslide reelection. The pogroms continued, as hundreds of thousands of Jews fled Russia, most heading for London or New York. With American public opinion turning against Russia, Congress officially denounced its policies in 1906. Roosevelt kept a low profile as did his new Secretary of State Elihu Root. In late 1906, Roosevelt appointed the first Jew to the cabinet: Oscar Straus, becoming Secretary of Commerce and Labor.[59][60]

Restricting immigration from Eastern Europe – 1924-1965[edit]

By 1924, 2 million Jews had arrived from Central and Eastern Europe. Anti-immigration feelings growing in the United States at this time resulted in the National Origins Quota of 1924, which severely restricted immigration from many regions, including Eastern Europe. The Jewish community took the lead in opposing immigration restrictions. In the 1930s they worked hard to allow in Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. They had very little success; the restrictions remained in effect until 1965, although temporary opportunities were given to refugees from Europe after 1945.[61]